The Art and Times of Cameron Stewart

A Shuster and Eisner Award-winning illustrator for his web comic Sin Titulo and recognized with multiple nominations for other Harvey, Eagle, Eisner, and Shuster Awards since 2007 for projects such as The Other Side, Seaguy: The Slaves of Mickey Eye, and Batman & Robin, Cameron Stewart began his now celebrated career as an inker. Following a chance encounter with Darwyn Cooke when Stewart worked in a Canadian video store and was doodling at the register, he began a professional apprenticeship under Cooke's direction. From there, Stewart graduated into shorter pencil assignments on DC Comics' Superman Adventures and Vertigo's The Invisibles in 2000. His first ongoing ink work, however, came about through a collaboration with writer Ed Brubaker on Dead Enders for Vertigo. Regular work continued from 2000 to 2001 with inking gigs on various Vertigo one-shots or specials, including Warren Ellis' Transmetropolitan, and Stewart subsequently began inking Cooke's line work on the iconic Brubaker-penned Slam Bradley and Catwoman stories in Detective Comics, followed by inking work on Swamp Thing and Hellblazer. Out of his association with Brubaker, Stewart moved on to inking Catwoman in 2002, as well as eventually designing covers and interior pencils for the series.

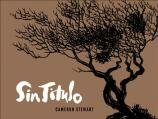

After cover and interior work for Dark Horse in 2003, Stewart cemented his partnership with Grant Morrison with the debut of Seaguy in 2004 and began working with Ray Fawkes on the first installment of Apocalipstix in 2005 (it was later developed into an original graphic novel by Oni Press). Returning to Morrison, Stewart completed the pencils, inks, and covers for the Seven Soldiers Manhattan Guardian miniseries in 2005 and united with up and coming first-time writer Jason Aaron on The Other Side in 2007. As the special features in the collected edition reveal, Stewart actually visited Vietnam to gain a better appreciation of the visuals and environment he would be replicating in the series—a practice he has maintained for Assassin's Creed in 2010. Audiences also experienced the first installment of Stewart's Sin Titulo web comic in 2007, an ongoing internet series written and illustrated by him that has produced 115 daily strips thus far. Since then, Stewart has maintained an intensive creative output with a second Seaguy series, a four-issue run on Batman & Robin, cover and interior work on IDW's Suicide Girls, and Assassins Creed, cowritten and co-illustrated with Karl Kerschl. I had the honor of moderating his 2011 Spotlight panel at Comic Con International in San Diego last year (from which some of the following interview is a direct transcript) and discussing his varied and prolific career. (And, no, he's not the brother of Kristen Stewart from Twilight, so please don't ask!)

Getting into your life before comics, I'd like to know a little bit about your background and involvement in art. Was it something you simply enjoyed as a child and later pursued on your own, or something you were driven to by a family member or influential teacher?

My grandfather was a cartoonist in the second world war, so I remember when I was a kid seeing drawings up on the wall of Hitler accidentally shaving his mustache off and things like that [laughs], and so I grew up with cartoons and comics. It's always been a thing I wanted to do.

Growing up in Canada, did you have exposure to both American and international artists or was it solely domestic Canadian comic artists?

Growing up in Canada, did you have exposure to both American and international artists or was it solely domestic Canadian comic artists?

I grew up with American comics, Marvel and DC stuff, but I also grew up in England. I lived in England as a child, because my family is all from England. I had exposure to British comics as well, such as 2000AD and kids humor comics like Dandy. I had an equal influence from both sides, I think.

Do you remember when the name of the artist on a title stood out for you and do you recall who was the first artist you connected with?

I definitely remember Brian Bolland being an artist I really gravitated to. I loved his Judge Dredd drawings and his covers for Animal Man. A very early sketchbook of mine from school is entirely filled with Brian Bolland swipes.

Since you had such diverse sources, and while enjoying comics is one thing and eventually making them is something different, when did you make a conscious decision to pursue it as a career, to be a professional comic illustrator?

Since you had such diverse sources, and while enjoying comics is one thing and eventually making them is something different, when did you make a conscious decision to pursue it as a career, to be a professional comic illustrator?

I think it was sometime in high school that I realized that people actually did this for a living and made money doing it [laughs]. It was an actual, valid career choice. I began to pursue it seriously then.

Recently, I learned that some artists began creating their own comics as early as high school as opposed to portrait drawings. What types of comic art did you produce during your high school years and what was your first original sequential art project?

I used to try to make comics all the time at school in place of doing actual assignments. If I had creative writing homework, I would draw a comic strip. The teachers usually loved the creativity of it, even though most of them were shamelessly plagiarized. The first completely original comic I drew was a short portfolio piece I took to my first San Diego con, about a fugitive clown framed for murder, called "Red Nose Blues."

From there did you go to art school and obtain a formal education then?

From there did you go to art school and obtain a formal education then?

I did not go to art school, which is funny because I've subsequently been asked to do lectures at art schools and the first thing that I say to audiences is "I didn't go to art school and you're all wasting your money" [laughs]. No, it was my own self study, and I read a ton of comics and copied drawings, training myself in the process. In a way, I kind of regret not going to art school because what I've done is trained myself to do one very specific thing, which is drawing black-and-white comic book-style artwork and I don't know how to paint. I mean, I can do digital color work, but I don't know how to paint with watercolors or oils or anything. I would really like to know how to do that and I'm sure, if I devoted the next 30 years of my life to learning it, I'm sure I could. I do wish I had a more broad base, but whatever, right? I've got a panel at Comic Con [laughs].

[Laughs] That's the lesson here then, kids: College is a complete waste of time. Go draw Batman.

[Laughs] Yeah.

What was your break then since you didn't have the outlet through a university setting, a gallery or sponsored art show like some other illustrators into professional comic work?

It was at San Diego Comic Con. I had written and drawn a little comic of my own that I self-published, by which I mean I photocopied at Kinkos [laughs] and stapled it together. I brought it [to San Diego Comic Con] and was showing it around. I brought them to artists whose work I really liked and asked for criticism, and everybody had really good things to say about it. I don't know if it's still the case, but it used to be that DC Comics had a lottery system for portfolio reviews and I won that lottery. I got my time with Shelly Bond at DC and she looked at my stuff and she really liked it, and she said that she thought I should be working professionally. So I went home and there was about six months where I didn't hear anything. I was almost on the verge of being totally despondent and working forever at the video store I was at, and she finally called and I was in. I was really excited because I got a call from DC Comics! I get to draw Batman! And it ended up that my first job was drawing Scooby-Doo [laughs]. But you're not going to say no to your first job! So I did it and I tried to see the positive side of drawing ghosts and haunted houses, and it ended up being a story of a haunted baseball diamond. I don't like baseball at all, so it was quite trying to get through it. It was a 10-page story and I was about six weeks late on it.

Wow.

Wow.

I'm much better now [laughs].

So was this before or after you began working as an apprentice for Darwyn Cooke? What types of projects did you work on for him?

I worked under him doing storyboards for the Men in Black animated series. He was a director on that show and managed to hire me on a freelance basis to draw boards. After that I didn't really work FOR Darwyn; we just shared a studio and he gave me a lot of invaluable guidance and advice as I was working on my own assignments. I was supposed to work directly with him on the Catwoman revamp with Ed Brubaker, but due to some personal conflicts, that fell apart, and I ended up on that book much later, after Darwyn's departure.

Since comics have their own inherent language of rhythms, beats, and the movement between pages and panels, where do you credit learning this process of developing a written script into a visual narrative?

Since comics have their own inherent language of rhythms, beats, and the movement between pages and panels, where do you credit learning this process of developing a written script into a visual narrative?

It's just something I've absorbed from a lifetime of watching movies and reading comics.

How do you then make the transition from light-hearted kids' fare comics into the harder-edged assignments with Vertigo?

Part of the portfolio I showed at SDCC included some Invisibles fan art I had drawn and Grant Morrison saw it. I had literally got in line to get his autograph and show it to him, and he really liked those drawings. I also showed those to Shelly, who was the editor of The Invisibles at the time, and the two of them talked and thought I'd be good at doing that. I only ended up doing a few pages in the series, but it was enough to get in there and have Shelly get me other work, like Dead Enders with Ed Brubaker, and from Brubaker dominoed into Catwoman.

Correct me if I'm wrong, but your first work here was primarily inking on Dead Enders, correct? While it was obviously your gateway into the profession, was inking something you were passionate about or was it, for you, a bridge into doing pencils and color assignments?

Correct me if I'm wrong, but your first work here was primarily inking on Dead Enders, correct? While it was obviously your gateway into the profession, was inking something you were passionate about or was it, for you, a bridge into doing pencils and color assignments?

No, I was just inking. I definitely…I mean, when I was 10 I didn't have dreams of being a comic book inker [laughs]. A lot of people really don't appreciate or understand what an inker actually does, and I certain didn't, really. Unless it's a rare case, I don't think you just break in and start pencilling. You have to learn the ropes a bit and pay your dues. It was really valuable, a really valuable experience spending a few years learning to ink properly, and now, even though I work digitally now, learning to ink properly with a brush was very important.

In that transition to digital, do you feel you've lost anything without the brush either in terms of the weight and power of the line? How do you try to replicate that digitally or do you just abandon that mindset entirely and do something completely different?

You gain and lose things, certainly. There's happy accidents that happen when you're inking with a brush that don't happen digitally, such as a little flourish of the brush and the bristles go in a weird way. It can end up working for you or against you. Sometimes it works really well. With digital, though, I have more control over that so you don't have those unexpected things, but the great thing I find in working digitally is that I take more risks. I know that any mistake is just a Command Z away from being fixed. I'm far more likely to just give it my all and throw a line down hoping it works and then just change it, whereas inking with paper, I was a lot more timid and that robbed the art of the spontaneity. I find that a lot of the digital work is actually, ironically, warmer and more spontaneous than some of the traditional stuff I've done. I use Manga Studio for the drawing and it's a piece of software that's specifically designed to draw comics. A lot of the brush algorithms are really good and they can replicate traditional inking really well. Half of what I show and post recently is digital and I don't know if audiences can tell the difference. The key is just even if you're working digitally to make it not look like it.

Since you started off inking and then moved into pencilling interiors, what did you learn in the process from the various writers and artists you worked with about the techniques of visual storytelling, plotting, and what your role could be beyond just laying down inks—how much you could contribute to the development of the project?

Yeah, it's funny because I have my own instincts and something I learned from writers, specifically Ed Brubaker on Catwoman, and it's not a knock on him at all, but I often thought he wasn't thinking visually. He would write scenes with characters that were very static and would be two characters sitting in a room talking or whatever or just climaxes in scenes that were just dialogue instead of fighting with characters that hated each other. And, in action comics, you want to see some action. I was pretty ballsy in Catwoman as I would redraw a scene not like it was written in the script and in doing that I thought I was honing my skills in drawing action scenes and making things look more visually dynamic on the page. That's what I took from that project. I always feel that when I'm working on a comic script with somebody else, the script is never set in stone. It's just a blueprint. I feel that as long as I'm maintaining the authorial intent of that scene, if I don't change where the characters have to end up, that I'm free to draw whatever I want as long as it gets the characters to the same point in the story. I feel that it's an artist's job and responsibility to bring whatever they can to it, to make it visually exciting on a page. Like I said, a lot of writers don't think visually in terms of what a comic page looks like. Some of them do, the best ones in fact do, but some of them don't. It's too dialogue heavy or they cram too many words in a page or whatever. That was the thing from Catwoman because we were actually constrained to the 22 pages every month and there was so much to put in, and I wanted to do all these elaborate action sequences, that I had to resort to drawing these really tiny panels that became a stylistic hallmark of the series. People would say, "Wow, that's a really unique look to the book how it ties the panels together, like Chris Ware type stuff" and that just developed out of a necessity to cram a lot of stuff into a small amount of space. That's actually become something I've enjoyed playing with now, finding all these little moments where I can insert into a page that doesn't have to be very big that add the necessary rhythm and flow to the story.

That reminds me, in terms of the busy-ness of a page, of the fight scene in Batman & Robin #16…

That reminds me, in terms of the busy-ness of a page, of the fight scene in Batman & Robin #16…

[Laughs] Yeah, that's a perfect example of where I had two pages to draw a fight scene with a hundred characters in it. I had no choice but to use the tiny panel approach.

Have you received feedback from your collaborators on your interpretation or deviation from the scripts?

Yeah and generally it's positive.

Well, that's always good [laughs].

I had a couple of clashes on Catwoman and you pick your battles. And I always feel that if I'm making a change to something that I have valid reasons for it and you just state your case to the writer and editor and say, "I think this will be improved if we do it this way" and maybe they'll agree and maybe they won't. Like in Catwoman, the climax of the storyline was Ed writing as two characters yelling at each other. And I was like, no, this one character has tormented Catwoman throughout this entire thing and when you get to that final showdown, you want to see Catwoman kick her ass. You don't want to just see them yell at each other. I proposed to Ed and the editor that we should strike this page of dialogue because it really doesn't have the same cathartic, climatic effect that a straight beat down will have. And I think initially, Ed, as a writer, was reluctant to lose a page of dialogue, but ultimately he went ahead and did it, and I think it works. Again, it's not a slam on a writer, but this is the process. Comics should be a naturally evolving, organic thing right up until the last moment; I think you should be tinkering with it and changing it. If it means somebody redrawing a scene or striking a page of dialogue and shifting around, right up to the end, anything you can do to make it more effective should be done. We shouldn't feel beholden that since it's in the script, we have to do it as artists.

Since inkers play such a critical role in defining light and shadow, depth, perspective, did that at all affect your approach to pencilling a comic, i.e., knowing and moving from the second stage of comics production back to the initial line art?

Since inkers play such a critical role in defining light and shadow, depth, perspective, did that at all affect your approach to pencilling a comic, i.e., knowing and moving from the second stage of comics production back to the initial line art?

Only inasmuch as I knew that I'd be inking my own pencils, and what I would and could achieve in that stage. It just made my pencils a lot looser. I have never had anyone else ink my work.

In regard to genre preferences, since you've worked in so many from spandex and military to science fiction and history, is there one that appeals to you more?

I like them all and I've never bought into the distinction between highbrow and lowbrow. I enjoy both things. I enjoy watching stupid action movies and I also like watching Lars Von Trier films. I very much enjoy doing a project like Sin Titulo, but at the same time love drawing Batman as well. What I like to do is follow one type of comic with the next so I'm not stuck in one place for too long. I like being able to hop back and forth, and I think I'm pretty fortunate that I have a foot in both spots and I can pretty easily jump back and forth between them. I really enjoy drawing action comics. It's pretty fun drawing that stuff and I get an emotional charge out of doing it. I'm interested in reading that stuff when it's done really well. I'm not terribly interested in reading superhero comics, weirdly enough, even though I'm known for doing superhero comics. People always ask me what types of comics I read and reading between the lines what they really want to know is what Marvel and DC books do I read. And honestly, I really don't, I really don't pay a lot of attention to that stuff for no other reason than it's just that there's a limited amount of time to take stuff in and I don't find that those things are to my taste anymore.

Regardless of genre, is it difficult for you to read comics then? Can you read a comic or graphic novel and simply enjoy it for what it is or does knowing about the process behind it ruin that experience?

There's definitely an element of deconstruction now when you read stuff. What's really great for me is when I read a comic and I don't think of that stuff. Like when I'm drawn into it completely and I'm not paying attention to stupid technical things as I'm reading it. The last thing I read like that was Chester Brown's Paying for It, which is great. That was a thing where I read it, I was completely absorbed in it, and I wasn't paying attention to the technical aspects of anything involved. It can happen. Actually, I really don't read a lot of comics, surprisingly. It's one of those things where cops don't go home and watch cop shows. I read novels, I watch a lot of movies…

Do you read your own work?

Hmm, yeah, yeah. Mostly because when I work on something and it's in black and white and unlettered, it's a collaborative thing, and I often don't see it until it comes back in printed form. Particularly in working with Grant Morrison on anything we've done. Grant works sort of Marvel-style where he gives us a script that's somewhat rough and loose and doesn't have final dialogue, so you draw it and then he scripts it afterward. When we get the box of comps, I'm quite interested to read it because I can go through and see the places where what I've drawn has influenced the dialogue and what he's written, and that's really cool. That makes it feel a lot more collaborative than just mechanically executing what he's done. Sometimes it's painful. Like any artist, I feel I have a bitter hatred of my own work [laughs].

[Laughs]

So quite often I look at stuff and just see the errors in it or the places where I wish I'd had more time to do this better or whatever.

Since you mentioned Grant's scripting style, is there one you prefer more as an artist?

I really enjoy working with Grant in that style because I enjoy the openness. The one problem of working with him sometimes is that there are times I read the final product and the dialogue is not what I thought it would be, so I go, "If I'd known that, I maybe would have drawn the scene differently." But I worked on the Apocalipstix, which is a book I created with my friend Ray Fawkes. For that he wrote it sort of like a movie script where the dialogue was there but he didn't do any page or panel breakdowns. He simply described what happened. From there, I had the freedom, say there was a car chase and a bus crashes, I had the freedom to draw 20 pages of that if I wanted, using my own instincts and my own sensibilities, I can get my own rhythm and sense of pace that I want rather than looking at a script and seeing Panel One: This Happens, Panel Two: This Happens, etc.

As you've moved into writing yourself either with Sin Titulo or Assassin's Creed, what have you taken from your understanding of how scripts work into your own writing process? Are there certain techniques you try to employ that you've learned from others?

It really depends on the project. Like working on Assassin's Creed, I was working for a gigantic video game company and they're very protective of that license, so they wanted to see a complete script before we started work on it. That was a case where they had approval every step of the way and we had to have an outline, and a first draft of the script, and all of it had to be approved beforehand. With something like Sin Titulo, I don't really script it. I sit there and I thumbnail it out. I have a template I use and it's always the same eight-panel grid, so I print it out and just sketch in the panel what each beat of the page will be. I usually start from the end because I know what the last panel of the page will be before the first one. So it's just a matter of sketching out the beats and sometimes I'll shift them around, or I'll move something. That's the writing process, even though I'm not writing words on the page. That is the construction of the scene. Once that's complete, once I have it locked down how the layouts go, I start drawing it. As I'm drawing it, I'm going over the dialogue or narration in my head so that by the time I get to the end and have the final art done, it's time to go in and do the final script. Doing it that way has been beneficial because I'll have the art and I'll write the dialogue and the dialogue will be too big and cover up a character or character's face. And what that does is force me to be really economical with the dialogue and I realize I've overwritten things and I have panels where they're over indulgent with dialogue or a clever line I think is great and it's often not [laughs]. There's been a lot of times where I have to cut lines of dialogue or streamline things, and it's always been better. It's an organic process where I massage it until it's exactly where I want it.

With this element of control, then, do you believe that the incorporation of digital tools into your workflow has allowed you greater creative outlets and means for such expression?

It's just the freedom to not feel like if I make a mistake, it's permanent. If I'm working on a Batman thing now, I often compose drawings in layers. I'll compose the background and a figure on one layer, another figure on a separate layer, and then I can move them around until I get them exactly as they should be in the panel rather than pencilling it all out and realizing, "Oh, this guy is too high" and then erasing it and drawing it again. I can do all these separate elements on different layers and then just move them and tweak them, and shrink it or increase it. I can add a foreground element or some object in the foreground just to see how it looks. If it looks good, great, I can leave it. If not, I can just remove it. That kind of thing, I think, leads to better work than I was previously able to do when I was working on paper. It's a greater freedom and flexibility. It helps me get stronger compositions.

Apart from adapting to a digital workflow, how do you continue to push or challenge yourself as an artist?

It's a constant thing. I push myself to be better by looking at my own artwork and see all the stuff I don't like about it. I look at others who are doing really great stuff and try to incorporate that.

Well, since you work in a studio, do you rely on your peers for commentary on your work?

Oh, yeah. Personally, I don't feel I'm strong at doing colors. I'm competent at it, but not exceptional. We have a fantastic colorist [Nadine Thomas] in our studio who did the Assassin's Creed stuff. I'm always asking her to come over and look at something I've done, and she'll identify something, say this part should be blue, and I'll change it, and she's always right. If you surround yourself with people you respect, you make sure you don't have any ego and that you're humble enough to take people's criticism, that will always result in improvement.

In terms of your own creativity, which works are you the most proud of producing?

The ones I've created are the projects I'm most proud of, so Sin Titulo, for example. It's the one I have absolute creative control on, it's all me and I do absolutely everything on it. That's what I won my Eisner Award for, and I think there's a connection there. It's the one I have the most passion for. The other I'm really proud of is the Assassin's Creed book, which sounds funny given it's a huge commercial juggernaut thing, but the really amazing thing about it is that we had total creative freedom on it. Even though it's a big commercial property, I'm very emotionally attached to it because they are characters that I did create and I wrote the story, and didn't have a lot of interference.

Do you think the venue and intended audiences for projects such as Assassin's Creed tend to sell more than traditional comics projects sold exclusively through comic shops?

Absolutely. The first issue was sold through Target and GameStop, and it was huge. The comic book store numbers were very tiny because video game comics have a bad reputation, and rightfully so in most cases, so a lot of shops didn't order it. But when you put a comic like that in an appropriate venue, it sells really well. I'm not saying that all comics should be based on video games [laughs]. There should be attempts made to sell comics beyond this small, insular community. Projects like Suicide Girls, which I was originally not supposed to draw but only do the covers for, but ended up drawing and getting my arm twisted to do so [laughs], opened up my art to an entirely different audience. I'm interested in not just hitting one market regardless of whether it's Assassin's Creed or Batman, and eventually have one moderately sized audience coming from all different places.

Because you do so many diverse projects, have you ever returned to the original portfolio comic you showcased here in San Diego? Did anything ever come from it?

Nothing [laughs]. I was like 20 or something, so it was not very good. It was about a clown who was framed for murder and was a fugitive from the police. It was called "Red Nose Blues" [laughs]. I did about 10 pages of it and I dug it out a little while ago, and it was cute, but wow…I think it's best left in the past [laughs]. It was successful enough that it got people interested in me, though.

I know we've discussed this before, and since Sin Titulo is essentially a digital comic that may eventually be collected into a hardcover prestige edition, but can you, as a producer of digital comics both creator-owned and in your work on corporate titles, give me your opinion on the development, which is still in its infancy?

I'm all for digital comics. I think they are—no, could be very, very successful. I'm constantly irritated at the failures of comic book publishers to harness this effectively. I think there's a lot of really dumb decisions being made that will prevent it from becoming as successful as they really want it to be. Piracy is a fear, of course, but it often feels that the comic book industry is one unpaid electric bill away from being shut down [laughs]. It seems like there's not a lot of long-term thinking, but instead "We've got to charge $3.00 for a digital comic because we have to make money on this right away" and they're not thinking that maybe, if you sold a million copies at .99 cents instead, it's better than selling ten thousand for more. It's still new and it's difficult to say. All I read is digital these days and I'm terrible, right, because I'm killing my own industry [laughs]. I try and buy digital comics when I can. At the moment, though, digital comics are basically print comics that are being ported over to an iPad. I don't think that's a great thing. I think eventually comics will be created with that device in mind and the power of that format in consideration.

Let me ask you then about digital comics and your own production techniques. Do you feel that digital comics, in working both traditionally with pencil and inks and now completely in Manga Studio, do digital comics reflect your artwork better or closer to what you envision the artwork should be than print mediums?

Absolutely yes, especially in coloring. Most comics are colored on computer screens these days and therefore are presented on a digital screen exactly how the colorist intended. There's always a difference in print comics where the colors are muted or dulled, and I've compared print comics with digital versions, and every single time I think digital looks better. That is entirely my own taste and I know there's nostalgia for the printed page, and I understand it. I think it's bulls---, but I understand it. I'm not being facetious either, but I think it's nostalgia and not actually a reflection of whether one is better.

Looking at Sin Titulo, it seems to be more of a traditional comic strip exported into digital format. Do you ever see yourself creating or producing sequential art specifically for a digital environment with the considerations of the devices being used to access it, page turns, etc.? Not necessarily motion comics per se, but something entirely different than basically digitized print comics?

Sin Titulo was definitely conceived as both. The reason it's horizontal, landscape format is because I knew it was going to be read on computer screens, but I also wanted it to work as a print comic, something to work in both formats. Doing it the way I have has allowed me to build an audience slowly and word of mouth travelled. Just realizing it flat out may not have that same steady growth. But I'd love to have a great big book and release it digitally.

When you step back and go over your career at this point, if you were to take on an apprentice as you once were for Cooke, what advice would you give or what lessons would you impart to them that were important for you in your growth and evolution as an artist?

Wow, that's a hard and good question.

Well, it's the last one, so it has to be [laughs].

It's a big one [laughs]. In terms of being a professional artist, you have to know what you're capable of. You have to know it's a business at the end of the day, so you can't be cavalier with deadlines. Learning discipline was something that was critical for my own artistic growth.

Are you a pretty disciplined artist today? Do you set yourself a daily and regular schedule?

Not in that sense. There's a natural ebb and flow of creativity you can't get around. There are some days where I just can't draw, but then I make sure I work harder the next time.

Although you haven't produced the quintessential Cameron Stewart project yet, is there one project that stands out more because it represented an awareness of medium, an evolution or growth in your development as an artist?

Sin Titulo, definitely, because it was my first serious move into creating something entirely on my own. It's my "auteur" project.

Lastly, since you've worked with so many varied writers and collaborated with such a diverse range of fellow artists, what has been the best criticism or validation of your craft that resonated with you?

Winning the Eisner for Sin Titulo—getting the top industry award for a book that was entirely my own creation was very gratifying.