Understanding Booth

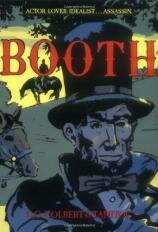

C.C. Colbert is the historian and author behind several books on American history. Booth, her first graphic novel, is a powerful reminder that history is complicated and multidimensional. Readers of Booth will learn not only about the notorious man behind the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, but also about his family, his friends, and his enemies.

Just why did John Wilkes Booth assassinate Abraham Lincoln? Colbert provides a scholarly and thoughtful response.

Colbert is also a strong newcomer and supporter of the power of graphic novels and comics to tell scholarly and literary-level stories: “The idea that comic books can only offer a simplistic vision clearly ignores dramatic evidence otherwise. A growing body of historical graphic novels such as [Emmanuel] Guibert’s Alan’s War boasts strong characters, vivid images, and powerful narrative arcs that clearly complicate and improve a story.” Here, she discusses the book and her work with GraphicNovelReporter.

In the Author’s Note, you write, “The scholar’s life can be isolated and frustrating. I have sometimes become despondent over the lack of scholarly resources available to bring my historical figures to life.” One of the most fascinating aspects about Booth is that your words do indeed bring John Wilkes Booth to life. Readers get to know John Wilkes Booth as an individual, a lover, a friend, a foe, a son, a brother, a spy, an actor, and, in his most familiar role, an assassin. How were you able to take the historically demonized and flat portrayal of John Wilkes Booth and breathe a full spectrum of life into him, a life that embraces him as both a passionate, patriotic man and as an assassin?

I have been working on the Civil War for several decades and one of the things about this field is that it does no good to demonize individuals. I was recently at a scholarly conference where one of my fellow Booth scholars was proclaiming the necessity to depict Booth as “bad” rather than “romanticizing” him. I am aware of his fears, but I have a very different perspective. Whether you are drawing a nonfictional portrait or inventing dialogue, a writer yearns for complexity—nothing flat and simple. It is perhaps more challenging, but more satisfying to provide content and texture: to portray a flesh and blood character, rather than a wax figure….

It is my goal to try to breathe life into those long dead, and to offer some kind of contextualization that allows us to see the world through our subject’s eyes…even if it is a distorted lens, it’s a perspective on events that commands our attention.

At times, Booth reads like a stage play, particularly in terms of its chapter divisions. Was this stagelike style intentional?

Absolutely. The Booths remain one of the most historically significant families within the annals of the American stage. I did want to pay tribute by trying to allow the drama to unfold as if the pages were part of a proscenium—and my brilliant artist, Tanitoc, caught the rhythm and spirit of this experiment. certainly suggest that John Wilkes Booth was self-conscious about his role within this theatrical family and American theater as a whole. He would have in some way viewed his life, especially the days leading up to the assassination, as one of his greatest performances—indeed a grand finale.

Why did you decide to tell Booth in graphic-novel format?

The graphic novel allows a fluid sense of narrative development, and this enabled me to imagine the story in visual terms. I do have to confess that so much of what appears on the page is a tribute to the genius of Tanitoc. He was able to transform my words into a series of visualizations that conveys mood as well as action. So having this full-blooded treatment gave the ideas some emotional wallop—essential for good storytelling. Thus the graphic novel seemed a natural for this conflicted tale of drama and woe.

Can you offer some insight into how you and your coauthor/artist, Tanitoc, collaborated to make the words and the images work so well together?

The artist has the tougher task, as the script comes first and the art follows. But this was really astonishing to me, to see how Tanitoc took my dialogue and directions, and fashioned my words into something gripping and gorgeous. Booth clearly projects the artist’s own singular contribution—and yet our book is a collaboration in which I can take pride as well. My story is so vividly complemented by his insight, and the lush images provided by our talented colorist as well.

One of the most engaging aspects of Booth focuses on Booth’s relationship with his family, especially his brother Edwin. A historical aspect that tends to get mentioned, and then marginalized, John Wilkes Booth’s familial ties (or lack thereof) take center stage in your story. As a storyteller, why go into such detail about Booth’s familial relationships?

As a storyteller, I keep in mind that all of us come from families and the push and pull of family affects us all dramatically—so playing on this theme comes naturally. Whether we are engaged or disengaged, our individual relationship to our family presents each of us with a connection to this subject, which is crucial. And I believe placing JWB into this dynamic illuminates his insecurities, even his demons, which can humanize the Civil War. We always talk about “brother versus brother,” but here is a real-life example, one of the most important case histories in our nation’s long history.

Many teachers will want to assign Booth to their students. If you were invited for a school visit what would you want to say to teachers and students about John Wilkes Booth? Why?

I would emphasize that Booth was only 26 when he felt it was necessary to take action—for his country, for his future—to eliminate the opposition. Booth’s violent action changed the course of history. He died a very young man—of whom much was expected. His role as assassin came as a deep shock to his theater family, to those who loved him, to those who had never imagined the depths of his feelings.

How and why he believed he was fighting for his country—even after General Lee surrendered and gracefully laid down his arms—remains a fascinating and forgotten facet of this era. Booth did not plan to kill the president after he issued the Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863, or even after the Thirteenth Amendment was passed in Congress in February 1865. Following Union victory, Lincoln hinted at black suffrage, especially for returning veterans, and it was this speech in early April 1865 that unhinged Booth and catapulted him down the path of destruction. So, as some have argued, Lincoln’s championing of black rights led to his death as a martyr to civil rights.

And by killing the president, Booth became more famous than any other actor of his generation, indeed any other actor in American history. His infamy, of course, spelt his downfall, as he ended his life alone and abandoned, with a sad message for his mother on his dying lips.

Booth does a delicate, brilliant job of portraying the ironic love triangle that seems to have existed between Lucy Hale, John Wilkes Booth, and Robert Todd Lincoln. What do you feel this love triangle brings to the story?

This love triangle is invented—and I was not very subtle initially and must credit my wonderful editor, Tanya MacKinnon, for her sure and steady influence, reining me in. If I would have included even half of Booth’s harem into the story, it would have been more of an octagon than a triangle—and certainly too much lust and emotion to follow. So I tried to imagine Booth as becoming more and more entangled into the snare of a passionate abolitionist, but also his perpetual backsliding as a bounder who used women who could not help but try to please him, as they found Booth a charismatic figure, and many saw him as a real life Romeo.

Your passion for telling this story was contagious. What can readers look forward to reading from you in the future?

Many stories, I hope. I am up to my elbows in a story about the tumult surrounding the creation and ratification of the Constitution. I am tempted to call it “No one thought it was a ‘Tea Party.’ ” But, once again, there will be villains and heroes and fractured, refracted personalities so we can understand the allure of the American experience.

Booth will, I hope, make some modest contribution to the historical literature—and spark some practical popular cultural interest…leading more readers to Manhunt, American Brutus, and other fascinating scholarly works.

I also have a dream to combine several of my interests to create a study of parallel and intersecting lives during the American Civil Rights movement, one of the most pivotal and powerful human dramas of the modern era.

-- Katie Monnin