Days of Thunder: An Interview with Dwight Jon Zimmerman

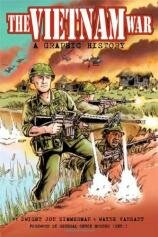

Early on in The Vietnam War: A Graphic History, writer Dwight Jon Zimmerman describes Vietnam as “ten thousand days of thunder that traumatized a nation.” Even more than three decades later, it’s obvious that is on exaggeration. This war, this event, traumatized our nation, both uniting and dividing it, sending it somewhere it had never been before. With a remarkably thorough way of explaining the entire scope of the war, Zimmerman has tackled a seemingly insurmountable project and made it so much more than a simple comic retelling of Vietnam. It’s a history lesson that truly teaches the depth of its subject. GraphicNovelReporter talked with Zimmerman about this massive undertaking.

What led you to take on the Vietnam War as a subject? And why as a graphic work?

When I was a kid, I was a big history/science fiction/comic book fan. When I broke into the publishing industry in the late 1970s, it was at Marvel comics; and actually most of my career in the industry was in the comics field. In the late 1990s, I found myself on the book side, working for Byron Preiss. It was thanks to Byron that I was able to finally professionally fulfill my passion for history, first as an editor, then as a writer.

I’ve wanted to do this project for a long time. I really wanted to do this. I was a kid growing up during the Vietnam War and some of the events I wrote about are things I recall seeing on television. The Vietnam War: A Graphic History is my first graphic history and my fifth military history book. In fact, the week that The Vietnam War: A Graphic History was released, the Military Writers Society of America informed me that my The Book of War won the 2009 Gold Medal Award for Reference. So this has been a great week for me.

Do you think this will be taken seriously as it’s intended, or could there be some who will dismiss it as a comic book?

We’ll find out real soon, won’t we? Certainly all of us working on the project took the responsibility of telling this history very seriously. I’m sure there will be some people who are knee-jerk dismissive of it because of the format, but fortunately this is no longer the bad old days of the late 1950s and early 1960s. One of the great things now is the wide acceptance of the medium. When you see The New York Times run serious articles about comics—and Google incorporate DC Comics superheroes into its logo for Comic Con International at San Diego—well, you can’t help but be happy and proud about the expanded acceptance and popularity of comics.

How long did it take to put this book together?

As Abraham Lincoln often said, “This reminds me of a story….” During my Marvel years, I became friends with George Roussos, who had worked for decades in the industry, mostly as an inker and a colorist. At one point in the 1970s, shortly after the corporation Cadence purchased Marvel from Martin Goodman, the new owners sent to Marvel a bunch of cost-efficiency analysts to get data on all the different aspects of comic-book production. One analyst poked his head into George’s “closet”—George preferred to work in a windowless room lit only by a lamp attached to his artist’s table—and upon seeing George finishing the painting of a color guide for a cover, asked George how long it took for him to paint it. George replied, “Twenty years.”

Of course, in actual time, George only took 15 or 20 minutes. But that 15 or 20 minutes was achieved as a result of 20 years of experience as a colorist. So, while the research and writing was around six months, you could say that this project took me about 40 years to write.

Americans have a complicated relationship with the Vietnam War. Do you find people understand it any better today than they did 10 or 20 or even 30 years ago?

This is a good question, and you’re absolutely right when you say that our relationship is “complicated.” Certainly we understand it better now than 30 years ago, because then the traumatic memory was so fresh that all anyone really wanted to do was forget about it. I think the passage of time has given us the space we need to better address what happened. Still, I found in the writing that some events of the Vietnam War remain “hot-button issues.” Keep in mind that our Civil War is still a passionate subject in some parts of the nation—and the shooting in that war ended more than 140 years ago!

You have an extensive résumé in military history. Were there things that you hadn’t known about the Vietnam War that you learned while writing this book?

Thank you for saying so! Since I had previously written about a number of events in the war, the subject was more familiar to me than it might otherwise have been. That said, I did find answers to a number of my own questions. Most of them had to do with the antiwar movement and demonstrations—both mainstream and criminal.

How did you take something so immense and complicated and condense it to fewer than 150 pages?

I’ve been asking myself that question.

I think this is where my experience as a comic-book writer came to the fore. Because a comic-book writer has such a small amount of space to work with, words, phrases, and sentences have to be crafted to convey the maximum amount of information in the minimum number of words. I was very focused on identifying “multilevel” events—in other words, events that simultaneously told more than one aspect of the war. This helped me compress the story of the war into the allotted pages. Then, having done that, it was easier—relatively speaking—to compose the script. Inevitably, there were things that had to be left out. That said, I think we succeeded in telling a more rounded story than people thought possible.

How did you come to work with Wayne Vansant?

I knew Wayne from my Marvel days and had the pleasure of being his editor on The Red Badge of Courage graphic-novel project when I was at Byron Preiss. He was on the short list of artists under consideration for the project and when asked my opinion of him, I said that I’d be thrilled to work with him.

How did you meet Gen. Chuck Horner and get him to write the introduction?

I got to know General Horner when I was working on Beyond Hell and Back, a history of pivotal Special Operations missions that I cowrote with John D. Gresham. I interviewed General Horner for our chapter about a mission that kicked off Operation Desert Storm. When it came time for us to have a foreword, I asked him. Fortunately, I caught him at the right moment in his busy schedule. Needless to say, having a four-star general participate adds a lot of credibility to this graphic history.

Do you see this as a book that could be used in schools?

Definitely. With The Vietnam War: A Graphic History, Wayne and I strove to make the story of the war accessible. I think we succeeded in that. I hope that it also prompts people to search out other books to learn more about events in the war.

Do you plan to speak to teachers or classrooms about the book?

I would love to do so. The graphic history just came out, so my publisher and I have yet to be contacted, but I look forward to any invitation to speak, either in person or through a blog, or skype, or other means.

You relate this book to current battles, particularly the war in Iraq. Do you think this will be seen as a political book? Would you like it to be?

Well, war itself is a political statement—the most violent one a government can make. And the Vietnam War was a very politicized conflict. That latter fact in particular put me on the “straight and narrow” to try and be as even-handed as possible. The war was so traumatic that promoting a personal agenda would have clouded rather than clarified the conflict.

Yet someone already has accused me of being political. But he so distorted parts of my text to support his assertion that I was compelled to write a correction to the blog where his comments appeared. As the late Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan said, “Everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not to his own facts.”

Would you like to do more nonfiction in this format?

Yes! In fact, I’m presently working on a script for a graphic biography for Hill & Wang and I hope to do even more such projects.

-- John Hogan